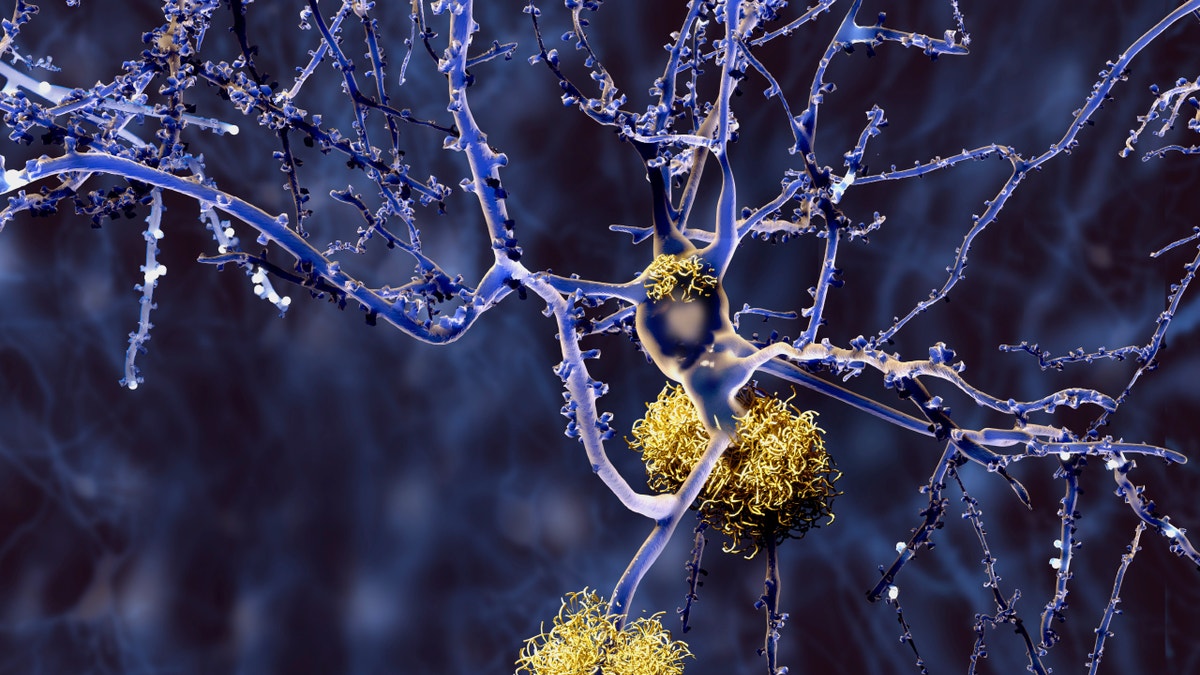

An image of amyloid plaques. (iStock)

In what some experts are hailing as a major breakthrough in the field of Alzheimer’s research, a new investigational drug was found to reduce the disease’s hallmark plaques— potentially slowing cognitive decline and preventing the disease.

Researchers cautioned, however, that the study was an early test for safety, and the drug needs to be tested further.

Alzheimer’s disease is marked by amyloid plaques, which are believed to be the main culprit in the most common form of dementia. Build-up of amyloid proteins leads to plaques, which blocks cell-to-cell signaling. In the trial by Biogen, researchers tested an antibody to see whether it can bind and break down amyloid protein, Time reported.

“We are pretty certain of the fact that the antibody reduces the amyloid plaques and in some ways gets rid of the majority of it,” Alfred Sandrock, senior author of the paper from Massachusetts-based Biogen, told Time.com. “That’s important because if we really want to treat Alzheimer’s at even the very earliest stages, then we felt it was important for our antibody to remove the plaque that’s already there.”

In the new yearlong clinical trial, researchers gave 165 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s monthly infusions of either the antibody, aducanumab, or a placebo, and did a series of brain scans. The people taking aducanumab showed a sharp decrease in the amount of amyloid beta in their brains. The higher the dose of aducanumab they received, the greater the amyloid clearance revealed in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

"After one year, you can see no red on the image, meaning the amyloid has almost completely disappeared," said Dr. Roger Nitsch, a co-author of the study and the director of the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Zurich. He is also a founder of the biopharmaceutical company Neuroimmune.

The findings, which have been publicly presented before, are being published Wednesday for the first time in a peer-reviewed journal, Nature.

“This is a remarkable therapeutic achievement and a tremendous advance for the field,” Robert Vassar, a neuroscientist at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois, told Science.

Additionally, participants who took the largest 10-mg dose showed less decline on one of two memory tests, compared to those who had lower doses or the placebo, Science reported. Researchers are recruiting for two separate 18-month-long phase III trials to see whether amyloid reduction will result in improved brain function , Time reported. Many promising Alzheimer’s drugs have failed in these larger groups, Science reported.

"We're encouraged that, there appeared to be a slowing of cognitive decline at a dose-dependent manner, and also a dose-dependent slowing in functional decline," said study co-author Dr. Stephen Salloway, a neurologist at Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island.

However, 40 patients dropped out of the trial, Science reported. Half did so because of adverse side effects, such as small hemorrhages or brain swelling. Higher doses more commonly led to the side effects. Individuals with a genetic predisposition to developing Alzheimer’s were found to be at a higher risk for developing brain swelling.

The larger question is whether clearing amyloid beta will lead to dramatic improvements in cognitive decline, Dr. Eric Reiman, a psychiatrist and researcher at Banner Alzheimer's Institute, a research and patient care center in Phoenix, wrote in an editorial accompanying the new study in the journal. Some researchers believe beta amyloid is a byproduct of the destructive brain process, and not the cause, noted Reiman, who was not involved in the new study.

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, which affects more than 5 million Americans, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

LiveScience contributed to this report.