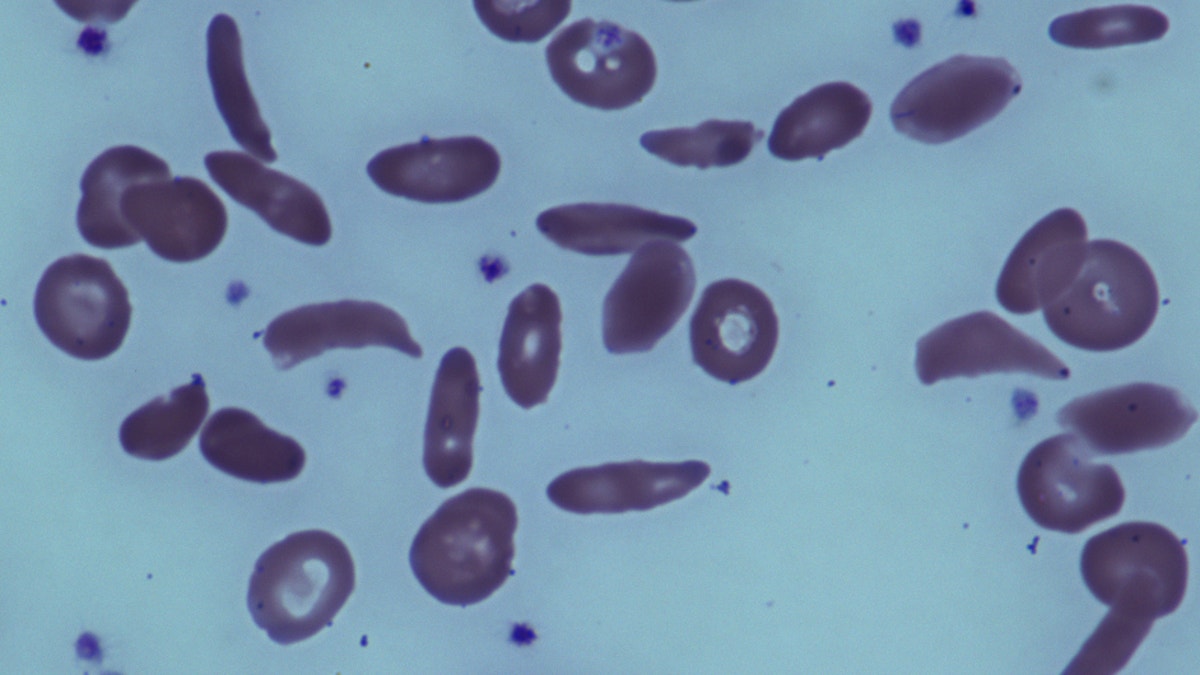

This image provided by the National Institutes of Health shows red blood cells in a patient with sickle cell disease at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md. (AP Photo/National Institutes of Health)

A French teen who underwent a first-of-its-kind procedure 15 months ago to change his DNA shows no signs of the sickle cell disease he had been suffering from. The procedure, which was performed at Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris, may offer hope to millions of patients who suffer from sickle cell disease, BBC News reported.

Sickle cell disease is a severe hereditary form of anemia, which causes patients to develop abnormal hemoglobin in red blood cells. The botched hemoglobin causes the cells to form a crescent or sickle shape, making it difficult to maneuver throughout the body. Sickle-shaped cells are less flexible, and may get stuck to vessel walls causing a blockage, which can stop blood flow to vital tissues.

Before undergoing the procedure, treatment for the unidentified teen included traveling to the hospital each month for a blood transfusion to dilute the defective blood, BBC News reported. According to the report, the excessive amount of treatment caused severe internal damage, and at age 13 he already needed a hip replacement and had his spleen removed.

In a world first, doctors at Necker Children’s Hospital removed his bone marrow and genetically altered it using a virus to compensate for the defect in his DNA responsible for sickle cell disease, BBC News reported. The results published in the New England Journal of Medicine said he no longer uses medication, and has been making normal blood for the past 15 months.

“So far the patient has no sign of the disease, no pain, no hospitalization,” Philippe Leboulch, professor of medicine at the University of Paris, told BBC News. “He no longer requires a transfusion so we are quite pleased with that.”

Doctors said the treatment will have to be repeated in other patients as the teen is the trial’s first, but that it does show powerful potential.

“I’ve worked in gene therapy for a long time and we make small steps and know there’s years more work,” Dr. Deborah Gill, of the gene medicine research group at the University of Oxford, told BBC News. “But here you have someone who has received gene therapy and has complete clinical remission – that’s a huge step forward.”

It was not clear how much the procedure would cost, or whether there are plans to expand to other countries.