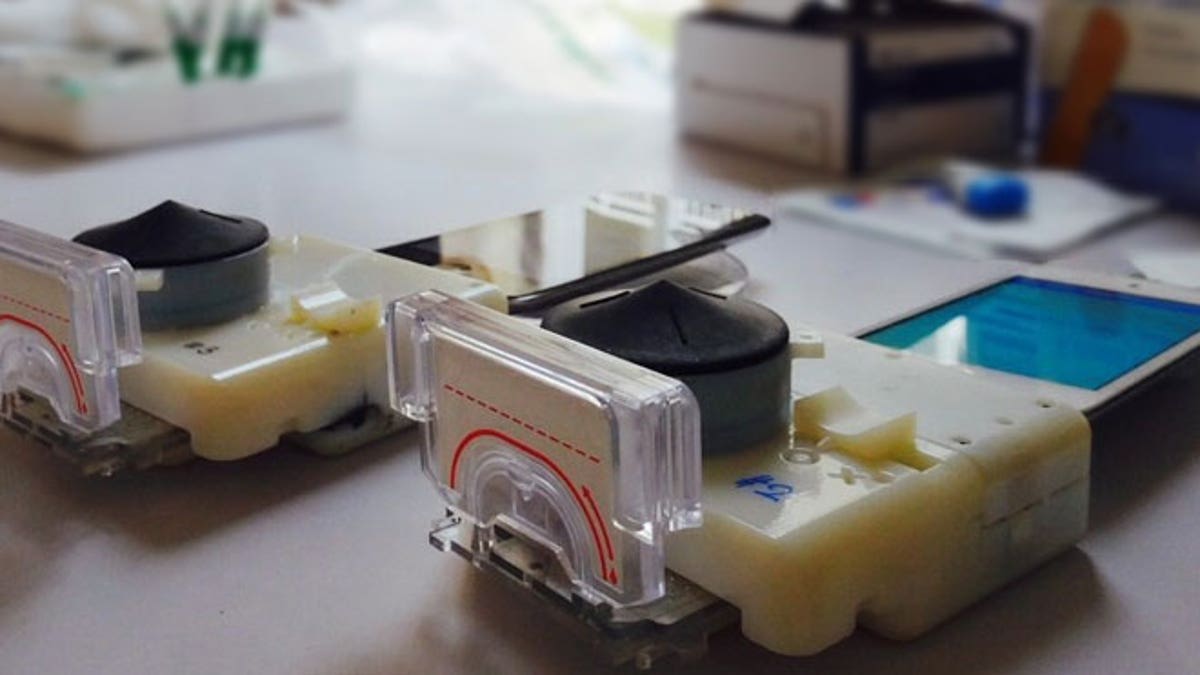

Smartphone dongles performed a point-of-care HIV and syphilis test in Rwanda from finger prick whole blood in 15 minutes, operated by health care workers trained on a software app. (Samiksha Nayak, Columbia Engineering)

Engineers at Columbia University have invented a smartphone accessory that can detect three markers for sexually transmitted diseases with a finger-prick. Compared to traditional laboratory tests administered in the United States and around the world, which can take days to deliver results, the dongle can tell if a person has either syphilis or HIV in only 15 minutes.

Researchers have already tested the contraption in Rwanda, where mother-to-child STD transmission is high, and they say it has the potential to facilitate diagnoses for STDS in other disease-zone areas of the world.

Inventors of the technology also say that it has the potential to one day transform these diagnostic tests in developed countries like the United States.

“In the U.S. actually, there’s a trend towards providing a lot of health care services away from hospitals— it’s infrastructure-heavy and expensive, and you really shouldn’t have to be there,” lead author Samuel K. Sia, biomedical engineering professor at Columbia, told FoxNews.com. “Catching diseases is about being proactive and preventative … [with these accessories] I think you could actually see a lot of savings, and more privacy and convenience.”

The smartphone dongle replicates traditional lab-based diagnostics for the HIV antibody, as well as two markers for syphilis— the treponemal-specific antibody and the non-treponemal antibody for active syphilis infection— in a single-test format. It does so by performing an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), a traditional STD test, with all of the power being drawn from the smartphone. That feature could increase its chances of success in places like Rwanda, where electricity isn’t always available, researchers noted.

The accessory tests for syphilis and HIV in particular because they are two serious infections that can be passed from mother to child in the womb, Sia said, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has highlighted these as priority areas for disease control as a result. According to the WHO, nearly 1.5 million pregnant women worldwide are infected with probable active syphilis every year. About half of them are untreated, which can lead to stillbirth, fetal loss and other devastating conditions.

“That doesn’t mean other STDS aren’t on the list— they are, and other non-STDs are,” Sia said of the dongle. “But these are priority because of the burden of disease and seriousness of disease, and how treatable they are.”

In a paper published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Sia and his colleagues detailed their trial of the accessory on 96 pregnant women in Rwanda who were recruited by word of mouth and with consent at local clinics. His team created a separate software app to help train local health care workers in administering the mobile test. They partnered with the local Ministry of Health, the Rwanda Biomedical Center, and the Institute of HIV Disease and Prevention and Control, among other groups, to carry out the trial.

Researchers held the tests at health care facilities in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, and targeted areas of the country that had a high incidence of HIV and syphilis.

“The device is very useful in our settings: cheap, easy and quick. At a large scale, it will save lives,” Sabin Nsanzimana, division manager of HIV and STIs at the Rwanda Bio-Medical Center and the Ministry of Health, told FoxNews.com in an email interview.

Researchers found the technology was 92 to 100 percent accurate for sensitivity, or tests that were true-positive, and 79 to 100 percent accurate for specificity, or tests that are true-negative.

Ninety-seven percent of the patients that were tested reported satisfaction, and the majority said so due to the easy procedure and the fast results.

Sia pointed out that despite the dongle’s satisfaction rates, the technology may raise patient privacy and data security concerns. The accessory itself is slightly larger than a USB dongle and plugs into the audio jack of a smartphone or tablet, but when a patient is tested, a memory chip is plugged into the dongle and that chip houses the test results. Making sure medics interpret that info correctly and keep it safe will be essential, Sia said.

“I think all of those are legitimate concerns, but overall, with the right safeguards in mind, there will be more pros than cons to having blood tests available to people in more settings,” he said.

Typical ELISA equipment costs about $18,450, but the dongle that Sia and his team have created costs only $34.

Sia said the technology has the potential to test for more than just STDs: “We can look at hormone levels, cancer markers, diabetic markers, disease markers.”

He added that the current portable health device trend holds promise for future tests like the one his team created.

“What we’re trying to offer here is going beyond these accelerometers which track your movement,” Sia said. "I think that’s when you’ll see the health care system fundamentally transformed for the better.”